A Pipe Dream Made Real – by Donald Lindsay

📷 Photos by Pip Graham-Bishop

Twenty years ago this January, I stepped into a journey whose full scope I couldn’t then imagine. The seeds were sown earlier, but the story began in earnest in 2006 when a grant from the Arts Trust of Scotland made it possible for the late Nigel Richard to prototype a keyless chromatic Scottish smallpipe chanter.

Nigel had already cracked the equivalent problem for border pipes. But smallpipes, being cylindrical, present different physical challenges. Still, he understood the principles — far better than I did at the time — and the prototype worked. I played it for six years, learning its possibilities.

It had a one-octave range, like most smallpipes. But I became curious: could that range be expanded, upward and downward, without adding keys?

I suspected that keywork had been largely rejected by Scottish pipers for good reasons — reasons rooted not just in aesthetics but in the tactile form of piping itself. Cylindrical reed instruments (like the clarinet or smallpipes) don’t naturally overblow into a second register the way conical ones (like the Uilleann pipes or saxophone) do. There’s a gap. To bridge it without disrupting the idiom — technically, ergonomically, musically — would take some doing.

So I began a quiet process of prototyping, always asking the same question: could this new design speak convincingly within the Scottish piping idiom? That meant judging every new note on its tone, its ergonomic placement, its role in the scale, and its implications for technique and repertoire.

By 2013, I’d discovered 3D printing. MakLab in Glasgow’s Lighthouse had just opened. One sunny afternoon, I watched the first Lindsay System prototype begin to emerge from the lab’s Ultimaker printer, using highlighter-green filament. Midway through, Glasgow saxophonist and tea-blender Martin Fell walked past, and leaned in to watch.

“What’s it making?” he asked.

“A chanter.”

He nodded, paused, and said in tones of awe:

“I’m looking at the future.”

He wasn’t wrong.

In 2014, a small Kickstarter campaign let me bring that future into our home. My wife Hannah, son Ryall (then 10yrs), and I watched the countdown from our kitchen in Pollok, South Glasgow. It was a moment of pure excitement, and possibility. By 2016, during Ryall’s October school break, the first fully playable Lindsay System chanter was born — stable, ergonomic, and tonally satisfying enough for professional use.

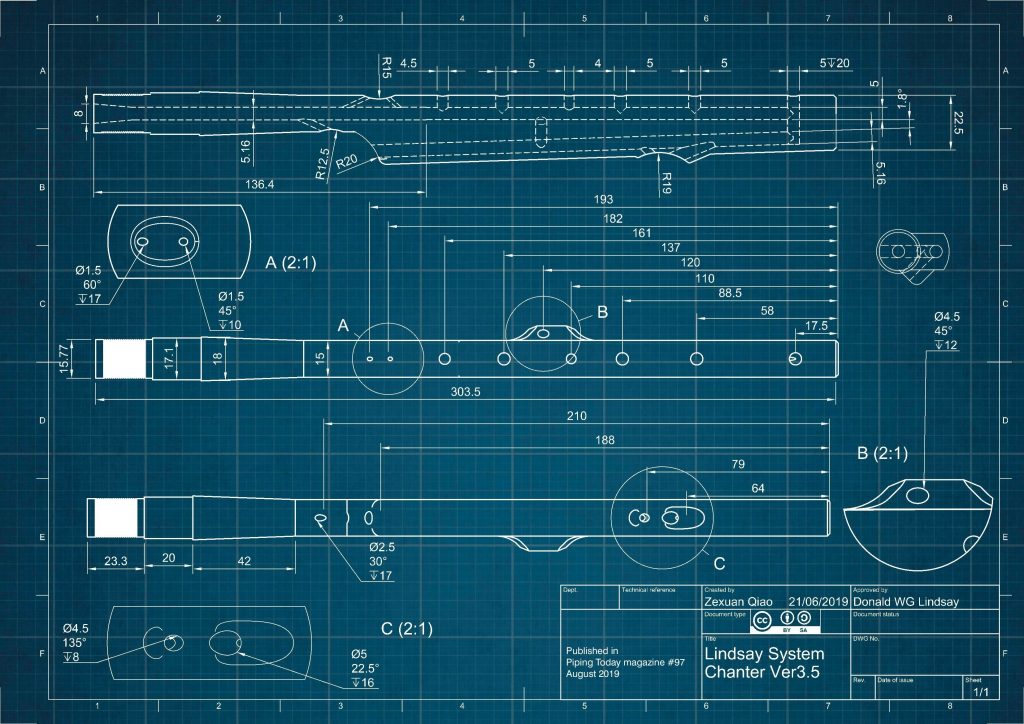

Blueprint: Draft drawing by Zexuan Qiao, based on models and data provided by Donald Lindsay. Originally typeset, colour graded, and published in Piping Today (issue 97).

Blueprint: Draft drawing by Zexuan Qiao, based on models and data provided by Donald Lindsay. Originally typeset, colour graded, and published in Piping Today (issue 97).

That final prototype marked a turning point. During development I’d used the same handful of test phrases all that week — short sequences to explore the stability and voice of the extended range. That morning, when I came downstairs to the kitchen with the finished print, they didn’t just function. They sang.

The first phrase climbed into the second register, tentatively but with a keening clarity — reminiscent in timbre of the Uilleann pipes, though still bearing the grain and warmth of smallpipes. The second tumbled downward across the new low end, stepping in and out of the traditional scale like round, mossy stones in water. A tune formed. I played it round and round, almost surprised that it kept asking to be played. That tune became Chanter 2, later recorded with a band at the College of Piping in Glasgow. It’s still on YouTube.

From there, development shifted outward. The following year, in 2017, Piping Today published the first of five articles on the project, written by Elizabeth Ford, documenting the system’s evolution and outlining its potential. Two early prototypes — The Rainbow Set of Pollok and A Phìob Ghrianach — were formally added to the Museum of Piping’s permanent collection in 2019. That same year I handed over my teaching work at the National Piping Centre and left Scotland with my family to live on Ascension Island – a remote volcanic island outpost, in the mid South Atlantic.

There, I focused on consolidation: design iteration, tone work, reed design, and the beginnings of a formal method. I also continued collaborating remotely with Zexuan Qiao, a young designer and academic who I’d met in Glasgow, then based in UCL in London, now at Queen’s University Belfast. Together we developed LSC_PRINT&PLAY — a downloadable, home 3D-printable version of the chanter that’s still available via Thingiverse. Zexuan contributed significant refinements to the internal bore design, including proposing the square-bore variant that ensures relative consistency of diameters across different printers and materials. That file set has now been downloaded over 2,500 times worldwide.

In 2018, I’d invited, and remotely mentored Malin Lewis — then a student at the music school in Plockton — to build the first wooden version of the Lindsay System chanter. Malin has gone on to do incredible things with the chanter, in performances and recordings, including the soundtrack of The Outrun in 2024, and their debut album Halocline, in the same year.

Since moving to Orkney in 2021, I’ve kept development in progress, quietly in the background. Our time here has been a lot busier than on Ascension – we’re renovating a house, somewhat slowly, and I’ve established an electrical contracting business locally, providing a vehicle to apprentice my son. Meantime, the system has grown in scope and reach, while remaining rooted in its original aims: musical clarity, ergonomic form, and cultural shareability.

The system remains open-source. All designs are released under Creative Commons. This isn’t just idealism — it’s a structural choice. I believe that traditional instruments, like traditional music, belong most fully when they’re made available to others. That belief and trust has largely been met with care, generosity, and rigour by those who’ve engaged with the work.

Next year, 2026, marks two milestones: twenty years since the first prototype conversation with Nigel Richard, in the festival club during Celtic Connections 2006, and ten years since the system graduated from prototyping – to the sound of Chanter 2. I’m planning a modest series of events and teaching days to mark that time — not to celebrate an endpoint, but to affirm a threshold. The work now has community around it – many of whom have invested deeply in the instrument and the design – and the next decade will reveal how, where, and why it is taken forward.

For now, the instrument is speaking, and singing, and growing, and next steps in terms of design development, music, and community building are being planned.

Download the home 3D printable version of the chanter:

www.thingiverse.com/thing:4271780

Sign up to receive Donald’s newsletter and keep up to date with his 2026 plans here.